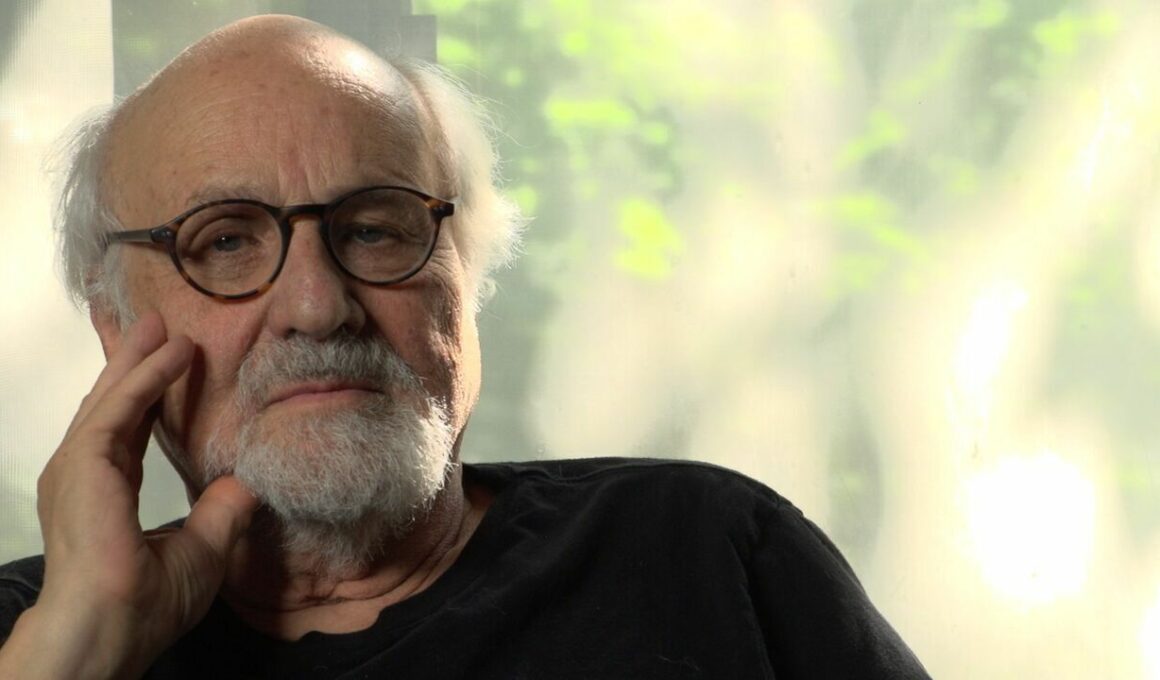

Morton Subotnick is one of the pioneers in the development of electronic music and multi-media performance and an innovator in works involving instruments and other media, including interactive computer music systems.

Most of his music calls for a computer part, or live electronic processing; his oeuvre utilizes many of the important technological breakthroughs in the history of the genre. His work Silver Apples of the Moon has become a modern classic and was recently entered into the National Registry of Recorded works at the Library of Congress. Only 300 recordings throughout the entire history of recordings have been chosen.

In the early 60s, Subotnick taught at Mills College and with Ramon Sender, co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center. During this period he collaborated with Anna Halprin in two works (the 3 legged stool and Parades and Changes) and was music director of the Actors Workshop. It was also during this period that Subotnick worked with Buchla on what may have been the first analog synthesizer (now at the Library of Congress).

The Buchla Suite: A Handcrafted Tribute to Morton Subotnick is the latest project and sound-exploration vehicle for Stefan Schultze’s Large Ensemble. The project was inspired by Morton Subotnick’s seminal composition Silver Apples of the Moon, which was released in 1967. Composer and pianist Stefan Schultze spoke to Morton Subotnick in preparation for his project.

Stefan Schultze: After a long time of planning and designing, what happened when you finally could work with the Buchla Synthesizer? And what were the implications?

Morton Subotnick: I worked with Don on the design of the Buchla for almost two to three years, explaining what I wanted it to do, and he would design it on paper. I knew I wanted to be able to make a new kind of music, a brand new genre of some kind, but I didn’t know what that would be other than it would be a machine to allow a composer to be a studio artist, much like a painter.

But, I imagined, if the machine we were designing would be capable of creating a very difficult piece of music, it would probably be capable of making something that would be completely new, a new kind of music, a new genre altogether. So, I took a page from the score of Boulez’s Le Marteau Sans Maitre that I considered to be the most difficult piece ever written. I worked on it with Don for two years without touching a knob or hearing a sound!

It was the beginning of 1966 when the Buchla was finally really finished, and delivered to us at the SF Tape Music Center. By then, I was soon to be moving to New York, and had a duplicate built and sent to my future NY studio.

It wasn’t until I got to NY that I could physically start really working with it. I quickly started realizing that I had made many mistakes. I began calling Don for revisions on existing modules and for new modules. As I worked and played with it the metaphor of a painter’s studio art became clear; what I would create in my studio would allow me to create, play, listen, make revisions and record on a tape recorder much like a painter brushing on a canvas. And, when done, the painter’s painting would be sold and hung on a wall of a person’s home or the wall of a museum. The music created as studio art would be mastered and duplicates would be distributed as a vinyl record to be ‘played’ on a phonograph player in someone’s living room or over the radio.

I realized that my music as studio art did not include performing live on a stage. I tried to do live performances but the technology was clearly a studio art and not well suited for public performances so I put that aside and pursued my vision of music for the record player, starting with Silver Apples of the Moon.

Stefan Schultze: So basically, it wasn’t just the pure decision to do something for a record medium. In the beginning it was the choice because you couldn’t realize it live yet?

Morton Subotnick: No, not really. I’m glad you asked that to straighten that out. I really wanted to be a composer as studio artist. And that was postproduction. I really saw that from the beginning, that it was like a painter. So, a painter finishes in his studio, everything is done and then he sends it out and it’s done. All the improvisation is done in the studio. That was my metaphor for this. I never even thought about a public performance live at that point. And it’s only that Silver Apples was so successful that people started asking me to do it. And that really meant that in a way, the electronic music as a studio art was even better than the painting because you have a player. It’s not just a painting you look at, but as an audience you could start anywhere you want. You can’t do that with a painting. Well, you do it a little bit, the way you look at it, but it was a perfect medium and you could make multiples of it. They’d still be the right thing. You make multiples of a painting and you’ve got reproductions that aren’t the real thing. So, to me, it really made sense. That’s what really triggered me to make me feel I was on the right track. Because in some ways, being a chamber artist, now everybody is with art, with music. They all do it in their bedrooms and wherever you are. But in those days, that was no possibility. And so, what I was after, was that. The Buchla was never intended for live performance.

Stefan Schultze: You defined yourself as a studio artist. Did you conflict with the terms composer/performer/improviser at that time?

Morton Subotnick: I have always had trouble with that. Even when I was writing for instruments. I started that when I was in high school or junior high school. I understood composer because I read the biography of Mozart and so forth. I knew what a composer was, and it seemed like I was being a composer. But when I began to deal with the electronics, I was always all these different things as a studio artist, as a painter is. Being a painter, it’s attached to a verb to paint. But to compose is a different thing. That’s not a verb. It really means to be a composer, sit down in your chair and compose the music. The composing is a mental thing. It never made sense to me once I thought about it, because you’re writing on a page and it’s very different. I’d suppose I do remember thinking at the time when I had the trouble with that idea that in some ways, Bach and Beethoven and Mozart and all these people, you see their original manuscripts and the notes are not straight down. They go to an angle. And this means that they were writing fast. It was handwriting. They were composing in a way they were performing, and they scratched things out and went back. So there was a little bit of change and it wasn’t direct. Mozart once said that he wrote the overture to Don Giovanni in two minutes. You can’t do that but I know what he meant. It’s a sense of, oh, I know what that piece is, and you just sit down and do it. And that becomes the composing. Not an improvisation because your brain knows what it’s going to be. You let the brain control the hand and you just go through it.

Stefan Schultze: When did you start performing live with the Buchla?

Morton Subotnick: I didn’t get to the public performance until 50, 60 years after I had done Silver Apples of the Moon. I kept testing the technology and somewhere around 2000 I began to realize that the home computers were getting close. And then it was in 2010 when we were doing Jacob’s Room. I had met Lillevan because he was going to do the live electronics with the visuals for Jacob’s Room. They wanted to make sure we had a young audience. So, they had brought me in to meet with Lillevan and we would do a small tour of performing with the Buchla, which I didn’t even have at that time anymore. I was working just in the computer with the ghost pieces. Don Buchla had just finished the 200 E. I helped him a little bit and he wanted me to have it. And I said, I don’t want to carry equipment with me anymore. But I thought, well, this time maybe I’ll do that. And so, I did it and it seemed like it was really, really fun and people liked it. And so I started getting interested as I finished the multimedia pieces in bringing that idea I had way back in 1968 of performing live, which had to be different from the postproduction thing. And so that’s when it started.

Stefan Schultze: How did it feel to interact live with the audience after so long?

Morton Subotnick: I just was sitting there and looking at the Buchla in public and they wanted us to do an encore. And I didn’t know what an encore was in those days. I hadn’t performed in public as a soloist for years at that point. So we did it and it was probably in some ways the most fun thing that Lillevan and I ever did. I think we did two encores. To me it was exhilarating. Suddenly all the stuff from 1965 came back and I was just having a wonderful time. And because we didn’t have anything prescribed, we were really looking at each other what we were doing next. And these were probably the best improvisations I’ve ever done in my life. It was really fun. Then I really addressed myself for that point to the public performance.

Stefan Schultze: How did the fact that you were a very talented clarinetist as a young musician influence your work with the Buchla?

Morton Subotnick: I was a well-known clarinetist as a kid, and so by the time I was in my twenties, people actually traveling through San Francisco came visiting me. The woodwind quintet from the New York Philharmonic came across. The clarinetists would come and take lessons from me twice my age, but I could do things that they couldn’t do, and I would give them lessons on how to do it. I was really a good performer, and it just came easy to me. I was okay as a composer. I was getting awards and things. And so that was pretty good. But when I got into the electronics, with the studio art, I realized partially that I was motivated because I could be the performer. I knew what it meant to be a good performer. It’s not a brain thing. It’s almost like I was good at acrobatics. My body was just very well organized, and that had nothing to do with me. I was just born that way. I had control over my fingers and my hands and things like that, that I could do trills across the things that were written in books that said it was impossible to do, that I was able to do as a kid. I didn’t know it was impossible, so I just did it. And I knew I could bring this aspect to the studio art. And I was aware of that when we were designing the Bucha.

Stefan Schultze: In modular synthesis, random values can be achieved by a sample-and-hold circuit with a white noise source. Don Buchla has developed the Source of Uncertainty module to control various degrees of unpredictability. What is your approach to working with and controlling randomness?

Morton Subotnick: When I worked with it, I didn’t know about white noise or anything. Buchla introduced me to all those ideas, so it was up to me to decide what to do with that. The early design didn’t have too much, but the later had it and he called it the module of uncertainty. But I didn’t want to do random. I understood from the beginning what that meant. The randomness at that level of human uncertainty, the random itself, just straight random is very boring. I had built in the idea of control over the amount of randomness in every parameter, the depth of the numbers and where they are. So you could go from zero to hundred, or from ninety to hundred. Or you could go from zero to ten, where it’s almost not random at all. I almost never open it beyond ten percent, but I’ll move the ten percent in different ways, so it’ll go zero to one randomly or in increments that are very similar. And that makes a big difference. A vibrato where the pitch changes from 0 to 0.5 is really beautiful. It’s not the randomness that we use with our voice. It’s a randomness that sounds like the voice, but it’s different and you can control it, and this is way back, we’re talking 1959 and 1960.

Stefan Schultze: When I listen to your music, a very big inspiration for me is that it sounds so gestural and completely organic. It feels a bit like a human body is moving through space. I don’t feel grid and a lot of times it feels very natural. Do you think that you can humanize a machine?

Morton Subotnick: Well, that’s a good question. I really never tackle that in public. It’s just too much to deal with. The idea of the organic part was the most important part for me that I wanted to introduce as one of the potentials of a new New Music, of the new thing. To me, that’s probably my contribution, that more than anything else is that what comes out is something that feels like it’s real, so that when the sound goes around the room or across the room, something else changes with it. It’s the ability to think of a sound as a live organism, in which case it has dimensions. So if you pull a rubber band and make it longer, like making a note longer, but all the dimensions get longer, it gets thinner and stronger. If you then pluck it, it has a higher pitch when it gets longer. All of these are dimensions of a sound. And that’s one thing I stress. Everybody can do that and make that. Whether they could be a good performer is something else. Basically you can’t say if you just use my equipment, you’re going to be just like me. Because we’re different people and I grew up at a different time. But that part of it, the organic part, was an offering. And I still don’t demonstrate that in public because it takes too long to talk about. But when I’m teaching, I teach them how to think about things as an organism and think of the parts of sound and the spatial movement and reverberation and all that kind of stuff as part of the dimensions. Think of it as a physical object and it has dimensions.

Stefan Schultze: That leads me to my last question. What advice would you give to young musicians working with electronics today?

Morton Subotnick: I really don’t have advice because I don’t know who they are. And they’ve grown up in a time very different from my time. My suggestion is to just for themselves to think of a couple of things. One is what they’re working with the plugins and all the stuff that they’re working with their computers, is to just think about what it was made to do and how many people are doing it that way. And how many are being sold. And if they can actually look up the number, you can find out how many it would be like, say suddenly you look it up and you figure that they’re selling about 10,000 a year. That would be a small amount. And you figure 10,000 people are getting exactly the same thing you were. That has all the limitations that you’ve got and you’re liking it and think that maybe 5,000, even a year are going to be doing exactly what you’re doing in your piece. Maybe not to the very last thing, but much more closely than any piano piece of people playing the piano with its limitations. Just to think about that before you think, oh, this is good, and then play it in public and realize someone else is doing something so damn close. And the other thing is to identify how much music, whatever it is for electronic or whatever genre you’re working with, how much you listen to, and really grasp the sound of it and what it is, and then listen to what you’re doing and see how different that really is. Then make your own decisions about where you want to go. But if they don’t do that, then they’re doomed because they’re going to be part of the mass doing the same thing.

One of these apps like TikTok comes up with a brand new idea. It suddenly makes it. And the reason is it’s a new idea. They’ve investigated. Nobody has done this before. And they do that. Not that you need to do that. It could be a decision you don’t want to do something different. But before you know that, that would be my suggestion to them. Just those two things.

Composer and pianist Stefan Schultze is one of the most multifaceted and original musicians to come out of the German jazz scene. A Berliner by choice, Schultze studied piano and composition in Cologne and in New York. He occupies the interface between new music, improvisation and jazz with which he has most definitely created his own style. His artistic projects cover a spectrum of compositions for small and large ensembles, from leading larger ensemble formations, to initiating and producing cultural-political music projects on national and international stages.

Stefan Schultze has founded and led a number of award-winning ensembles and worked with many important musicians and orchestras such as Tom Rainey, Herb Robertson, the Metropole Orchestra and the WDR Big Band. In 2015, Deutschlandfunk produced his album with the Chinese sheng soloist Wu Wei, followed by “Ted The Bellhop” in 2017. With long-term cooperation partners such as the Goethe Institute and the German Foreign Office, he has completed concert tours and residencies worldwide. Stefan Schultze is the director of the Master’s program for Music Composition Contemporary Jazz at Bern University of the Arts, Switzerland and he is leading various university orchestras, master classes and workshops.